ICI Viewpoints

How America Supports Retirement: No, Benefits Are Not “Tilted” to the Higher Earners

Second in a series of ICI Viewpoints.

In my new book, How America Supports Retirement: Challenging the Conventional Wisdom on Who Benefits, I analyze the benefits individuals receive from the major government policies that help American workers accumulate resources for retirement: Social Security and tax deferral on compensation set aside for retirement in employer-based plans (both traditional pensions and defined contribution plans, such as 401(k) plans).

Existing research on who benefits from these programs typically examines them in isolation, which paints a misleading picture of the retirement system. As I explain in the first ICI Viewpoints in this series, the Social Security benefit formula is progressive, replacing a higher percentage of pay for workers with lower earnings. Social Security is designed to be the primary retirement resource for such workers, while workers with higher earnings rely more on distributions from retirement plans to supplement Social Security benefits.

Research and policy discussions that focus only on the benefits of tax deferral ignore the important role played by Social Security and emphasize the fact that higher-earning workers derive larger benefits from tax deferral, both in dollar terms and as a share of their income. The result is a myth that I tackle in my book:

- Myth: The retirement system is regressive—that is, its benefits are tilted heavily toward higher-earning workers.

- Fact: The benefits of the retirement system are progressive. When benefits are measured as a percentage of lifetime earnings, lower earners benefit more from Social Security and higher earners benefit more from tax deferral. The combined benefits of the two programs, however, are proportionately higher for workers with lower lifetime earnings.

Measuring with the Same Yardstick

To measure the combined benefit of Social Security and tax deferral, I needed a common yardstick. Previous research has measured the two programs differently: the benefits of the Social Security system are calculated on a lifetime basis as net benefit payments (the present value of benefit payments minus the present value of Social Security payroll taxes), while the benefits of tax deferral are usually estimated on an annual basis as a tax expenditure (actual taxes paid compared with the taxes that would be levied if tax deferral weren’t in the tax code).

My common yardstick: measure the benefits of both programs as tax expenditures, over the lifetimes of six representative workers with a range of incomes. To do that, I ran three simulations, calculating:

- each worker’s lifetime net tax liability (the present value of all income taxes and payroll taxes paid, minus the present value of Social Security benefit payments received) under current policy, with Social Security and 401(k) plans as currently constituted;

- each worker’s lifetime net tax liability if tax deferral were eliminated and the worker used the same amount of pay (including both employer and employee contributions, after taxes) to fund a taxable, rather than a tax-deferred, investment account; and

- each worker’s lifetime net tax liability if both tax deferral and Social Security were eliminated and the worker used both 401(k) plan contributions and Social Security taxes (employer and employee shares, after taxes) to fund a taxable investment account.

Tax Deferral: The Misunderstood Basics

Before I present the results, I should explain how tax deferral works. Many policy discussions imply that tax deferral provides the same benefits as a tax deduction (such as the deduction for mortgage interest) or exclusion (such as the exclusion for employer-paid health insurance). But a deduction or an exclusion affects a taxpayer’s bill to the IRS only once: in the year that the mortgage interest is paid or that the health insurance is provided. Tax deferral affects a worker’s taxes in three time periods:

- When employers or employees contribute to a plan, the contribution is excluded from income (taxes are reduced).

- When the plan’s assets generate investment income, that income is excluded from income (taxes are reduced).

- When the worker withdraws funds from the account, usually in retirement, the entire withdrawal is included in income (taxes are increased).

Although the up-front benefit of tax deferral is the same as a deduction or an exclusion, the net benefit of deferral is a more complicated combination of three partially offsetting effects. In simple terms, a taxpayer who defers income has to give part of the benefit back. A full accounting of the benefit requires that one calculate tax liability over a worker’s lifetime—which is what I do in this study.

The Benefits of Tax Deferral Are Flat Across a Wide Range of Income

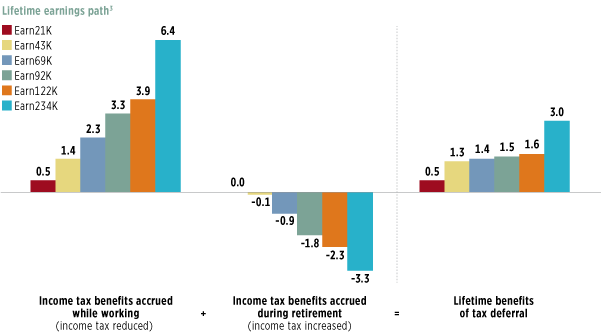

The first figure measures the benefits of tax deferral by comparing the results of the first two simulations.

Figure 1

Present Value of the Benefits of Tax Deferral by Lifetime Earnings

Benefits of tax deferral expressed as the present value of the net reductions in taxes paid because of tax deferral1 as a percentage of the present value of total compensation2 earned from age 32 through age 66 for representative individuals with various levels of lifetime earnings

1 In the absence of tax deferral, it is assumed that 401(k) plans would continue to exist but would be treated as taxable investment accounts. For assumed contribution behavior, see Figure 2 in this ICI Viewpoints. Contributions to 401(k) accounts are assumed to be invested in bonds earning 3.0 percent plus inflation, with accumulated assets used to purchase an actuarially fair, inflation-indexed, immediate life annuity upon retirement.

2 Total compensation is the sum of wage and salary earnings, the employer share of payroll taxes (both old age, survivor, and disability insurance [OASDI] and hospital insurance [HI]), and employer matching contributions to 401(k) plans.

3 The lifetime earnings paths of the representative workers are based on the earnings paths derived in Brady 2010. See this ICI Viewpoints for additional detail.

Note: Components may not add to the total because of rounding.

Source: ICI simulations

The leftmost set of bars shows the benefits that workers get from deferring tax on compensation contributed (either by the employer or by the employee) to their retirement plans while they are working: the tax savings from excluding contributions, as well as the investment income generated by those contributions, from their measured income. As a percentage of lifetime earnings, the tax savings rise with earnings—increasing from 0.5 percent for Earn21K, the lowest-earning worker, to 6.4 percent for Earn234K, the highest-earning worker.

The middle set of bars shows the costs (i.e., the negative benefits) that most workers incur from tax deferral in retirement: the increase in taxes caused when one includes all distributions—both contributions and investment returns—in income. (The lowest-earning worker, Earn21K, pays no tax in retirement with or without tax deferral.) As a percentage of lifetime earnings, the tax increases rise with earnings: from 0.1 percent for the worker earning $43,000 per year, to 3.3 percent for the worker earning $234,000.

Note that the workers who got the biggest tax reductions while they were working also experience the largest tax increases in retirement. So when those two effects are combined, the lifetime benefits of tax deferral—shown in the third set of bars—are relatively flat as a percentage of lifetime earnings. Lifetime benefits range from 0.5 percent of lifetime earnings for the lowest-earning worker, to 3.0 percent for the highest earner. For the other four workers, benefits vary only from 1.3 percent to 1.6 percent of lifetime earnings. What’s striking is that these four workers span a large share of the earnings distribution: at age 40, Earn43K is in the 46th percentile among all workers aged 35 through 44 ranked by annual earnings, while Earn122K is in the 92nd percentile.

(The causes for this pattern of lifetime benefits are complex—which is one of the reasons my book is so long. As the next piece in this series will explain, however, this pattern is not caused by the workers’ marginal tax rates.)

The lifetime benefit estimates illustrate why policy discussions that focus solely on the up-front benefits of tax deferral are misleading: for the highest-earning workers, tax deferral has a larger impact on the timing of taxes than on the total amount of taxes paid over their lifetime. More than half of the tax benefit they accrue during their working years is reclaimed by higher taxes in retirement.

Lower Earners Benefit More from Social Security

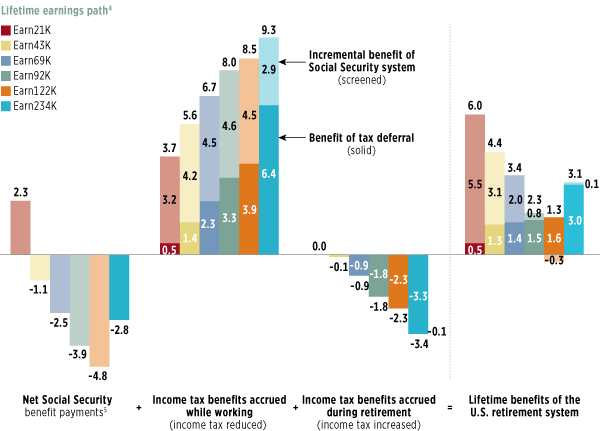

The figure below shows the benefits of the combination of Social Security and tax deferral, calculated by comparing net tax liability in the first simulation (the current tax and transfer system) with net tax liability in the third simulation (replacing both Social Security and tax deferral with taxable investment accounts). It’s complicated, so let’s walk through it step by step.

Figure 2

Present Value of the Tax Benefits of the U.S. Retirement System by Lifetime Earnings

Benefits of the U.S. retirement system expressed as the present value of the net reductions in taxes paid because of tax deferral1 and the current Social Security system2 as a percentage of the present value of total compensation3 earned from age 32 through age 66 for representative individuals with various levels of lifetime earnings

1 In the absence of tax deferral, it is assumed that 401(k) plans would continue to exist but would be treated as taxable investment accounts. For assumed contribution behavior, see Figure 2 in this ICI Viewpoints. Contributions to 401(k) accounts are assumed to be invested in bonds earning 3.0 percent plus inflation, with accumulated assets used to purchase an actuarially fair, inflation-indexed, immediate life annuity upon retirement.

2 In the absence of the current Social Security system, it is assumed that Social Security would establish a system of taxable individual investment accounts. Social Security taxes (both employer and employee share of old age, survivor, and disability insurance [OASDI] taxes) are contributed to the investment accounts. Investments are assumed to be the same as with 401(k) accounts (see note 1).

3 Total compensation is the sum of wage and salary earnings, the employer share of payroll taxes (both OASDI and hospital insurance [HI]), and employer matching contributions to 401(k) plans.

4 The lifetime earnings paths of the representative workers are based on the earnings paths derived in Brady 2010. See this ICI Viewpoints for additional detail.

5 Net Social Security benefit payments are calculated as the net present value of benefit payments received less the net present value of taxes paid (both employer and employee OASDI taxes).

Note: Components may not add to the total because of rounding.

Source: ICI simulations

Net benefit payments from Social Security: The leftmost set of bars shows one component of the benefits of the Social Security system as a percentage of lifetime earnings: net benefit payments, which is the difference, in present value, between the benefit payments that a worker receives and the Social Security taxes that a worker pays. Net benefit payments are steeply progressive—positive for the lowest-earning worker, but negative for all others. The impact is muted for Earn234k, the highest earner, because only about half of this earner’s wages ($117,000 in 2014) are subject to Social Security taxes and counted in calculating Social Security benefit payments.

These bars present the measure of benefits used in previous studies of Social Security.

Social Security’s impact on income taxes: To make Social Security’s benefits consistent with the tax expenditure measure used to measure the benefits of tax deferral, however, I had to include the impact of Social Security on income tax liability. As shown in the lighter portions of the second set of bars, Social Security reduces income taxes substantially for all six workers—in fact, the effect is larger than that of tax deferral for all but the highest-earning worker. This is because, without Social Security, the employer’s share of Social Security payroll taxes (6.2 percent of pay) would be included in a worker’s income and subject to tax, as would all the investment income generated from contributing both employer- and employee-paid payroll taxes (a total of 12.4 percent of pay) to a taxable investment account.

As shown in the third set of bars, Social Security has little effect on taxes paid in retirement—only Earn234K would pay more taxes (0.1 percent of lifetime earnings) if Social Security were replaced by taxable accounts.

The net lifetime benefits of Social Security: The lighter portions of the fourth set of bars combines both net benefit payments and the impact on income taxes from Social Security. They demonstrate that the lifetime benefits of the Social Security system are high for the lowest-earning worker, but decline steeply as earnings increase. For the two highest-earning workers, Social Security has little net impact, with the benefits of lower income tax liability roughly offset by negative net benefit payments.

The Combined Benefits of Social Security and Tax Deferral Are Progressive

So what is the distribution of the combined benefits of Social Security and tax deferral?

The last set of bars shows the combined effect. The lowest-earning workers enjoy the largest benefit from the combination of Social Security and tax deferral: 6.0 percent of lifetime income. Benefits decline as earnings rise for the next four workers, to as little as 1.3 percent of lifetime income for Earn122K. Benefits bounce up to 3.0 percent for the highest-earning worker. (Again, the causes for the pattern of the lifetime benefits from tax deferral are complex, but as the next piece in this series will explain, the pattern is not caused by the workers’ marginal tax rates.)

This fits the definition of a “progressive” system—one that weighs its benefits more heavily to the lower end of the earnings distribution. These simulations demonstrate that, as a percentage of lifetime earnings, Social Security provides more benefits to lower earners than tax-deferred retirement plans provide to higher earners.

In my next ICI Viewpoints, I’ll address the reason why higher earners reap greater benefits from tax-deferred retirement accounts. Hint: it’s not the reason that’s most commonly cited.

Additional Resources:

How America Supports Retirement

Other Posts in This Series:

- How America Supports Retirement: Tackling the Myths that Surround Us

- How America Supports Retirement: No, Benefits Are Not “Tilted” to the Higher Earners

- How America Supports Retirement: What Do Tax Rates Have to Do with the Benefits of Tax Deferral? Less Than You Think

- How America Supports Retirement: The Incentive to Save Is Not Upside Down

Peter Brady is a Senior Economic Adviser at ICI.