Money Market Funds: Lessons from Five-Plus Years

Brian Reid

Chief Economist, Investment Company Institute

March 11, 2013

Money Market Expo 2013

Orlando, FL

As prepared for delivery

Thank you, and good morning to everyone. I’m delighted to be here at MMX and to have the chance to share my views with you.

As I was preparing for this morning’s talk, my first thought was “what can I say that is new?” As I’m sure most here know, ICI and its members have been engaged in a highly public dialogue about money market funds since 2007. That makes it hard to find something fresh on the subject.

But a friend recently asked me, “What have you learned in the past five years about money market funds?” And that gave me a fresh start on this speech.

I have learned more about the short-term markets and money market funds in five years than I had learned in the prior 20 years at ICI and as a staff economist at the Federal Reserve Board. I have also learned that some policy proposals can be far more complex than what they seem on paper.

But the most important lessons for me have been not been about the economics of the markets and funds—but about the regulatory process. Five years ago, I thought that was a simple four- step process:

- Potential regulatory issues are identified by the industry or regulators;

- Regulators propose reforms;

- Then, various constituencies provide comments and present data and arguments in favor or against the proposals.

- Finally, the regulator uses those comments to arrive at rules that it believes will achieve its public policy goal.

What I have come to learn is that this textbook explanation doesn’t capture several important factors in the policy process. So this morning I want to fill in the blanks and discuss three key elements about policymaking that I have learned firsthand over the past five years.

- First, how an issue is framed is critically important in how people think about it. “Framing” is a term used by social scientists to describe how people select and assemble facts. Faced with a new situation, people have a natural tendency is try to fit the facts into an existing mental model or analogy—and to ignore the facts that don’t fit. Framing is critical to how people think about any issue.

- Second, eyewitness recall depends on the perspective of the observer. This was famously captured in the Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 movie “Rashomon.” In the movie, a crime is recalled by three different observers. Their recollections, of course, are very different based on their own perspective. You can find a similar dynamic at work in the policymaking process.

- Third, as regulators and commentators ponder an issue, they put forth solutions that come from their own experience. Regulators each have their own expertise. Each regulator is likely to favor those solutions that they are already applying to the organizations that they regulate.

All three of these elements relate to the importance of “story.” In early 2009, I had lunch with a former boss who warned me: “How the story about money market funds is told will affect policy for decades to come.” He was right—and we’ve been struggling with that insight ever since.

Let me begin with my first lesson, which is the importance of framing. Faced with a complicated new event, people reach for familiar mental models to help them understand. Mental models or analogies fit a complicated topic into a box that’s easier to grasp—particularly as you try to communicate to a wide audience including journalists, academics, policymakers, and commentators.

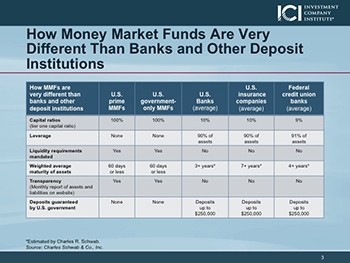

The mental model that has been used to frame money market funds is banking. Because investors can move money in and out of a fund, typically at a $1.00 share price, money market funds have been equated to banks.

Some regulators have taken this framing one step further—they promote the idea that money market funds practice “shadow banking.” The idea is simple: If money market funds are banks, but don’t have bank-like regulation, they must operate in the shadows. This pernicious epithet has grossly distorted the debate over fund reform.

Of course, that mental model isn’t accurate. To begin with, money market funds are extensively regulated and don’t operate in the shadows—they are in fact far more transparent than banks.

As inaccurate as I believe the framing is, it can’t be ignored. Indeed, ICI and its members have devoted much effort to pushing back on this false analogy.

As an example of how we’ve pushed back, last summer Charles Schwab took out a full-page ad in the Wall Street Journal in which he explained the vast differences between money market funds and banks.

As shown in the middle column, banks have modest amounts of capital , heavy leverage, no explicit liquidity requirements , long-dated, illiquid, non marketable loans, with significant credit risk, and almost no transparency about their assets and liabilities.

These features make banks vulnerable to runs by depositors, requiring banks to have access to a lender of last resort and to have their deposits guaranteed by the U.S. government.

By contrast, as shown in the first two columns, money market funds are investments. That is, the shareholders of the fund hold a pro rata interest in the fund, making the fund shares 100 percent capital. If a security in the fund suffers a significant loss of value, the investors in the fund can lose money.

Money market funds are not leveraged, have requirements to maintain mandated levels of liquidity, and hold short-dated, liquid, high-quality, marketable securities with minimal credit risk. They publish their portfolios monthly, and they are not guaranteed by the U.S. government.

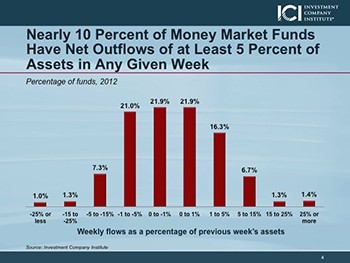

Because money market funds hold such liquid portfolios, they can accommodate substantial fluctuations of investor flows. For example, as shown in this slide, in any given week during 2012, nearly 10 percent of money market funds had outflows of at least 5 percent of their previous week’s assets—the three bars to the left in the chart. More than 2 percent of the funds in any given week had outflows exceeding 15 percent of their previous week’s assets.

Money market funds routinely accommodate these types of flows because their portfolios are constructed with short-dated securities that trade in liquid and diverse markets. That type of volatility in a bank’s balance sheet would cripple it.

Now, what fund sponsors learned during the financial crisis is that during periods of stress, markets can freeze up. As a result, ICI and its members supported the Securities and Exchange Commission’s 2010 reforms that increased liquidity of funds and enhanced the ability of funds to accommodate large investor flows and not disrupt the short-term markets even during periods of financial stress.

This was demonstrated during the summer of 2011, when investors pulled money from prime money market funds out of concern about the U.S. debt ceiling and European financial crisis. As ICI reported in a study published in January, funds easily accommodated those outflows: liquidity levels barely budged, and mark-to-market prices for most funds moved no more than 1 or 2 basis points. The liquidity requirements did improve the resiliency of money market funds and prevented spillover into broader markets.

The mental model equating money market funds with banks wasn’t accurate in 2008—and it’s even less accurate today. Yet this framing persists in the minds of some policymakers.

I’d like now to move to my second key lesson. As I mentioned, the “Rashomon effect” refers to the film classic that involves three eyewitness accounts of a heinous crime. The movie, of course, prompts the viewer to ponder where the truth lies.

In many ways, the story lines about money market funds and the financial crisis offer the same challenge. How an observer remembers the events depends on the vantage point.

Let’s take one group of eyewitnesses: the Federal Reserve.

The Federal Reserve stepped in to provide liquidity to the financial markets throughout the 2007–2008 crisis.

Recently, the President of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, William Dudley, gave a speech that presented his observations on the financial crisis and need for potential reforms.

What troubled me about the speech was a disconnect between the problems he described and the solutions he focused on. While he discussed concerns about the money markets broadly, he focused a significant portion of his speech on reforms for money market funds. The clear suggestion was that money market funds were the primary source of pressure in the repo and commercial paper markets during the financial crisis.

Dudley described problems both before and during the crisis. He asserts that “extensive use of short-term funding” prior to the financial crisis caused risks to be mispriced and interest rates to be too low. While Dudley doesn’t explicitly mention the supply-side effects of money market funds, his focus on money market fund reforms implies that these funds were the primary source of supply-side factors.

This is a common theme among central bankers and even some securities regulators. Adair Turner, Chair of the UK Financial Services Authority, has explicitly linked money market funds to the expansion of credit in the short-term markets.

Now, what distinguishes the financial crisis from the movie Rashomon is that in the financial crisis, we have data—much of which come from the Federal Reserve itself. For example, we can look at the pattern of interest rates before the crisis to test Dudley’s theory that excessive short-term credit caused markets to misprice risk.

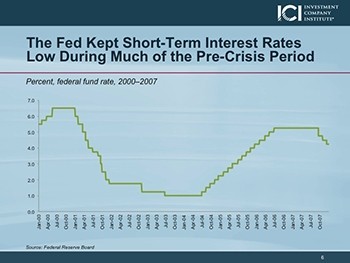

As you know, the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee sets monetary policy, and it uses the federal funds rate to anchor other rates in the short-term markets. The Fed is far and away the dominant player in these markets. As traders say, “never bet against the Fed.” This slide shows how the Federal Reserve lowered the federal funds rate 11 times in 2001, pushing it from 6.5 percent to 1.75 percent. For nearly three years, the Federal Reserve held short term interest rates below 2 percent. It did so to encourage businesses and individuals to borrow, consume, and invest.

To argue that an excessive supply of short-term credit from the private market distorted risk premia ignores the key link between Federal Reserve’s monetary policy actions and market interest rates.

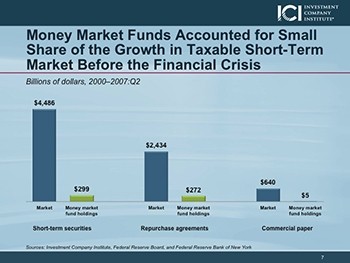

We can also look at data on how much of the growth in taxable short-term credit came from money market funds. This data was in ICI’s comment letter to the Financial Stability Oversight Council, or FSOC. Even if the supply of credit did have some effect on the overall short-term interest rates, this data show that the increase in taxable money market funds’ holdings prior to the financial crisis cannot credibly account for that expansion.

As the largest bar in the slide shows, from the beginning of 2000 to mid-2007, taxable money market securities expanded by $4.5 trillion. At the same time, taxable money market fund holdings of this short-term debt increased by only $299 billion.

Similarly, the repo and commercial paper markets grew substantially during this period — yet, money market funds accounted for only 11 percent of the growth of repos, and less than 1 percent of the increase in the commercial paper market.

During this same time, a wide range of other products and services, such as bank collective investment trusts, short-term investment funds, and other unregistered cash pools with constant net asset values, supplied a large share of the increase of credit to these markets. Yet none of these products merits a mention in President Dudley’s speech.

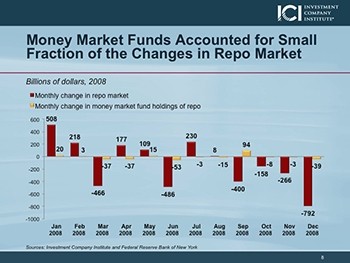

In his speech, Dudley also implied that money market funds were the primary source of pressure in the repo and commercial paper markets during the financial crisis.

The evidence is to the contrary—it demonstrates that investors other than money market funds often sharply pulled back from short-term markets.

During March 2008, when Bear Stearns was rescued by J.P. Morgan Chase with the assistance of the Federal Reserve, the repo market contracted by $466 billion. Money market fund holdings of repo decreased by $37 billion.

And, during September 2008, the repo market shrank $400 billion. In that case, money market funds did not contribute at all to the contraction: instead, money funds increased their holdings of repurchase agreements, by a little over $90 billion during that month.

Even during the week between September 16 and 23, money market funds expanded their lending in the repo market by $67 billion. Clearly, some investors other than money market funds had to account for the pullback in the repo market and the subsequent difficulties of financial institutions in obtaining this type of short-term wholesale funding.

During the last four months of 2008, the repo market shrank by $1.6 trillion. During this same time, money market funds increased their supply of credit to the repo market by $44 billion. As Professors Gorton and Metrick of the Yale School of Management have observed, money market funds provided credit in the repo market while other investors fled.

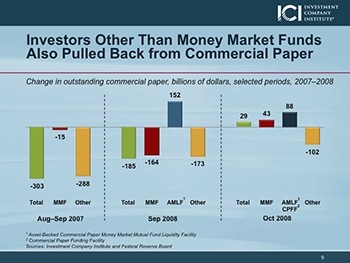

This chart tells a similar story for the commercial paper market. Once again, the data contradict Dudley’s implication that money market funds were the prime cause of the pullback.

As you all will remember, the commercial paper market went through a rapid contraction in the summer of 2007—shrinking by $300 billion in August and September 2007. As the bars on the left show, investors other than money market funds accounted for 95 percent ($288 billion) of that decline.

After the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, the commercial paper market rapidly contracted again. Investors began to pull back on Monday, September 15—following the announcements of Lehman’s collapse and Bank of America’s rescue of Merrill Lynch. CDS on financial institutions shot up that day as investors became unsure which institution would fail next and if the government would let it fail. Issuance of commercial paper with maturities beyond one week all but dried up, particularly for asset-backed commercial paper and financial paper. Rates backed up quickly for asset-backed commercial paper on September 15 and 16—before money market funds experienced substantial outflows.

The center bars tell the story for the month of September as a whole. Commercial paper outstanding declined $185 billion. Money market funds reduced their holdings by $164 billion. Investors other than money market funds reduced their holdings by more than $170 billion. The Federal Reserve’s Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF) offset about half of the pullback in the market.

The commercial paper market continued to contract through much of October, even though money market funds became net buyers during this time. It was not until the Federal Reserve’s Commercial Paper Funding Facility, or CPFF, became operational in late October that outstanding commercial paper started to expand.

For the month of October as a whole, total outstanding commercial paper grew by $29 billion with money market funds increasing their commercial paper holdings by $43 billion. As is evident, other investors continued to pull back from this market and more than offset money market funds’ purchases in October.

I’ve thrown a lot of data at you. But the message is clear. Unlike the hapless court in the movie Rashomon, we don’t have to rely on testimony from a narrow perspective. President Dudley’s focus on money market funds and by implication that they account for much of what happened in short-term credit markets before and during the financial crisis is clearly contradicted by the data.

My third and final key lesson involves what all the framing and storytelling lead to: policy outcomes or solutions. I’m sure you are all familiar with the saying that “When you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” I’ve often thought of this saying over the last few years. It’s become clearer to me how policymakers each have their own expertise, and thus tend to gravitate toward solutions that they know.

For example, the Financial Stability Oversight Council recently made three recommendations for money market fund reform. Now, five of the 10 voting members of the FSOC regulate banks or other types depository institutions. It shouldn’t be surprising that two of the FSOC’s recommendations would apply bank-style regulations—in both cases, a form of capital.

In a bank model, different investors and creditors bear risk in turn. Losses are first borne by equity holders of the bank. Additional losses are borne by the uninsured creditors. Finally, if losses are greater than these two groups can bear, the FDIC and ultimately the federal government enter to absorb losses and make the insured depositors whole.

Regulatory proposals advocating capital for money market funds miss several key points. A big one is that money market funds are not banks. Remember Charles Schwab’s full-page ad in the Wall Street Journal. Gains and losses in a fund portfolio pass to the investor. And while some fund advisers have stepped in and supported their funds, each and every prospectus of a money market fund makes clear that a money market fund is a security product and that losses are possible.

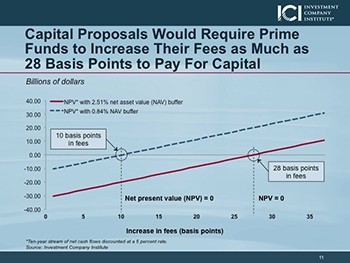

Second, a capital requirement on a money market fund would concentrate the fund’s risks on a small group of investors, rather than spreading it out across all shareholders. Investors who agree to absorb these concentrated losses in the fund will need to be compensated, and the remaining shareholders will have to pay them for taking on this risk. That payment would mean higher fund fees.

ICI has calculated what that payment would be for certain levels of capital. In one of the FSOC proposals, the typical prime fund would have to have a capital buffer equal to 2.5 percent of its assets. As the slide shows, using a net present value calculation, such a level of capital would require a fee of 28 basis points over and above the current fees on the funds, to pay for higher capital over a 10-year horizon.

Meanwhile, other funds—including Treasury money market funds and such unregistered cash pools as bank collective investment trusts—wouldn’t face similar higher fees. The result—FSOC’s capital proposals would render prime money market funds uneconomical, even when interest rates return to more normal levels.

The bank regulators have also advocated combining capital with a minimum balance at risk (MBR), where each fund investor would have a certain portion of its account held back upon redemption for a certain period of time. This holdback would be the first to absorb losses if a fund experienced a loss.

This concept starts with a capital requirement—which, as I’ve already said, tilts the economics against money market funds. But the MBR also would deny investors complete access to their fund shares. And it would make money market funds less liquid than other investment pools, including other mutual funds, or even a portfolio of repos and short-dated commercial paper and time deposits.

The MBR also creates serious operational issues for funds, intermediaries, and investors that would reduce or eliminate the usefulness of many services that money market funds provide.

Not surprisingly, investors have reacted negatively when surveyed about such a proposal. For example, about a year ago ICI sponsored a survey that Treasury Strategies fielded to institutional investors. As you can see in uppermost pie chart, the survey found that 90 percent of the respondents said that they would stop or decrease their use of money market funds if those funds had redemption holdbacks. Treasury Strategies estimated that total corporate assets in money market funds would decrease by 67 percent if such a proposal were adopted.

Now, it’s only natural that FSOC, dominated by banking regulators, would reach for a banking solution to the risks that it perceives in money market funds. But that solution—capital in one form or another—simply doesn’t work when applied to these funds. It’s a lot to ask, but regulators must set aside their preconceptions.

So, to wrap this up, here again are three lessons I’ve learned in my work on money market funds the last five years:

- Framing the story matters;

- Perspective on events matters; and

- Solutions will flow from experience.

As an economist, the thread for me that runs through each of these lessons is the importance of good facts and analysis. On big matters like money market funds, we will frame stories differently, we will perceive events differently, and we will reach different conclusions on what the best solution is. That’s just human nature.

But the fact remains, that the financial crisis was broad-based, and the stresses were often concentrated on the short-term markets. Single-minded reforms targeted at one product or group of investors will not make the markets more resilient.

ICI and its members have supported efforts to bring reforms to the tri-party repo market. Those market-wide reform efforts were the correct approach, and only policies that are focused on the markets generally will make short-term markets more resilient in the future.

Thank you, and I look forward to your questions.