ICI Viewpoints

Getting the Numbers Right on Investment Advice for Retirement Savers

As the Wall Street Journal noted this morning, ICI has deep concerns about the data used in a White House memorandum to support the Department of Labor’s push for tighter standards for financial advisers who help investors in employer plans—such as 401(k)s—and individual retirement accounts (IRAs). The same data points have found their way into the Administration’s speeches and materials for the rollout of potential new rules.

To elaborate on the Journal’s reporting, our concerns fall into three categories:

First, the Administration argues that brokers and other financial advisers are encouraging workers and retirees to shift assets out of 401(k)s and into IRAs so that the advisers can reap higher fees. If advisers were following that plan, one would expect IRA investors to be steered into higher-cost mutual funds.

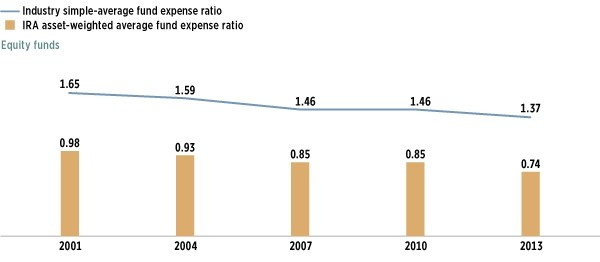

In fact, ICI’s data show that IRA investors tend to concentrate assets into lower-cost funds. As the chart below shows, the asset-weighted average fee that IRA investors pay (the bars) for equity funds is far less than the simple average fees charged by funds (the line). This pattern also holds true in hybrid and bond funds. For equity funds, the simple-average fund fee is 137 basis points, or 1.37 percent of assets, while the asset-weighted average paid by IRA investors is 74 basis points, or 0.74 percent. (Though the simple average encompasses the entire fund universe, the asset-weighted average more accurately reflects where IRA holders are investing their money.)

IRA Investors Pay Below-Average Fees

Note: Data exclude mutual funds available as investment choices in variable annuities.

Sources: Investment Company Institute and Lipper

If brokers are following a business model based on steering customers to costly products, they seem to be missing the mark.

Second, the White House’s illustration of a 401(k)-to-IRA transfer vastly exaggerates the difference in fund expenses paid by 401(k) investors and IRA holders (see pages 17 and 18 of the White House memorandum). The memo’s hypothetical illustration assumes that the investor is paying fund expenses of only 20 basis points when the money is in a 401(k), but will pay 130 basis points when the money is moved to an IRA.

As we’ve just shown, however, the average fee paid by IRA investors in a stock fund is 74 basis points—far short of 130 basis points. And the average fee for investing in stock funds paid by 401(k) investors is actually 58 basis points. So the real difference in fees, based on what investors are actually paying, is 16 basis points—much less than the 110 basis point difference claimed by the White House. Though the memo acknowledges that the example is hypothetical, this 110 basis point difference helps drive its estimates of multi-billion-dollar harm to investors.

Our data do show that 401(k) investors are paying lower fees in mutual funds than IRA holders pay. That most likely reflects economies of scale, as employer plans aggregate the savings of hundreds or thousands of workers. In addition, some IRA investors pay for additional services that aren’t included with 401(k)s—such as professional investment analysis—through fund fees. Taking away the ability to pay for those services may mean that some IRA investors get no help at all—which could be the most costly outcome.

Third, the White House memorandum asserts that a string of academic studies it relies upon can demonstrate that investors whose advisers are not subject to fiduciary duty suffer worse performance and pay higher fees than investors whose advisers are fiduciaries. I’ve read these studies, and they don’t support that conclusion.

The White House study and the research it references do not address the issue of whether investing with a nonfiduciary adviser costs more than investing with a fiduciary adviser. In fact, with the data available, they can’t answer that question. They can measure the cost of particular investments—but they don’t have data to capture the full cost of investing, including fees paid directly to advisers.

That’s a subtle difference—particularly in comparison to the data errors highlighted in my first two points. But it illustrates the need for rational, reasoned, fact-based policymaking on this important issue.

Brian Reid was Chief Economist of the Investment Company Institute.