ICI Viewpoints

Why Long-Term Fund Flows Aren’t a Systemic Risk: Understanding the Data on Institutional and Retail Investors

Third in a series of Viewpoints on long-term funds and systemic risk

In two previous ICI Viewpoints posts, I discussed the muted response of investors in long-term funds―which invest primarily in stocks, bonds, or both―to financial stresses, and examined some of the characteristics of funds and their investors that help explain that muted response. Researchers studying this topic, however, sometimes stumble over a key data issue: that the long-term mutual fund assets held in “institutional share classes” are not the same thing as long-term fund assets held by institutions.

The distinction, though seemingly arcane, is important. Researchers have sometimes used the assets and flows of institutional share classes as a proxy for the investment behavior of institutions. More recently, analysts at the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements have used this approach in an effort to explore whether and how long-term mutual funds might pose any kind of systemic risk.

It is inappropriate, however, to use institutional share class assets as a proxy for the holdings of institutions. It is likewise inappropriate to use the assets only in retail share classes to assess the behavior of retail investors. The reason, as I’ll explain, is that institutional share classes primarily hold assets of retail investors.

A Look at Share Classes

A mutual fund can be sold in multiple share classes, differing in terms of distribution channels and fees. A given fund will typically have a mix of share classes—retail, institutional, retirement, administrative, and others—to serve a range of clients.

Institutions—including insurance companies, defined benefit pension plans, businesses, banks and broker-dealers trading for their own accounts, hedge funds, and state and local governments―can and do invest in long-term mutual funds. When they do, they usually select an “institutional” share class.

What makes a share class “institutional”? There is no standard definition. Typically, though, a fund will specify an institutional share class as one having a very high minimum-balance requirement (e.g., $1 million or more) and often a low expense ratio. Each fund defines its own share classes, but some third-party data providers define institutional share classes as those having a minimum-balance requirement of $100,000 or more. A “retail” share class is generally defined as a share class that has a low minimum initial balance requirement (e.g., $2,500).

The term “institutional share class” can be confusing because, in fact, the vast majority of the assets in institutional share classes are holdings of retail investors. For example, mutual fund balances in individual retirement accounts (IRAs), 401(k) plans, and individuals’ nonretirement broker-based accounts are often invested in institutional share classes. Balances in these kinds of retail accounts are often pooled into a single “omnibus account” to meet the high minimum-balance requirement—and obtain the typically lower fees—of an institutional share class. Alternatively, some funds simply waive the high minimum-balance requirements of institutional accounts for retail investors who purchase shares through broker-dealers, 401(k) plans, college savings plans (such as 529 plans), and other channels.

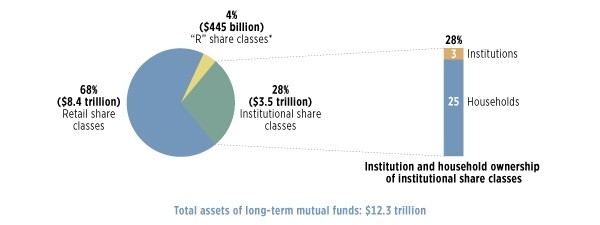

To illustrate, we split the assets in long-term funds into retail and institutional share classes (see the figure below). Of the $12.3 trillion in assets in long-term funds in December 2013, $3.5 trillion—or 28 percent—was invested in institutional share classes. But most of this $3.5 trillion was held by retail investors through 401(k) plans, IRAs, and other distribution channels. Only about 10 percent of the assets in institutional share classes—or 3 percent of total assets—were held by institutions, most of which reflected the holdings of businesses (probably mostly small businesses).

The Majority of Long-Term Mutual Fund Assets Are Held by Underlying Retail Investors

Percentage of total long-term mutual fund assets; year-end, 2013

* “R” shares include assets in any share class that ICI designates as a “retirement share class.” These share classes are sold predominantly to employer-sponsored retirement plans. However, other share classes—including retail and institutional share classes—also contain investments made through 401(k) plans or IRAs.

Note: Institutional accounts include financial and nonfinancial businesses, nonprofits, state and local governments, and other unclassified accounts. Accounts held by fiduciaries, retirement plans, and 529 plans are considered to be retail accounts.

Source: Investment Company Institute

In some ways, the confusion between institutional share classes and institutional assets is understandable. After all, monthly data—including that collected by ICI—is collected in terms of share classes. It’s more complicated to collect data based on the underlying ownership of fund assets. But once a year—during our Annual Institutional Survey—ICI asks fund companies to report assets held in various share classes by the type of underlying investor, even if those assets are held in omnibus accounts invested in institutional share classes.

To sum up, researchers should be very cautious about using the assets and flows of “institutional share classes” to infer investment patterns of institutions—doing so is generally inappropriate. For the same reason, researchers should resist using the asset and flows of “retail share classes” to infer the investment patterns of retail investors. By doing so, they exclude one-quarter of all long-term fund assets—the retail assets held in institutional share classes.

Sean Collins is Chief Economist at ICI.