ICI Viewpoints

A ‘Modest’ Proposal That Isn’t: Limiting the Up-Front Benefits of Retirement Contributions

Third in a series of posts about retirement plans and the policy proposals surrounding them.

In two previous Viewpoints posts (post one and post two), I explained the benefits that workers get from deferring tax on compensation set aside for retirement. The key insights from those posts are that:

1. Tax deferral is different from tax deductions or tax exclusions.

2. Tax deferral affects taxes over an extended period of time.

3. The benefit of tax deferral is not the up-front tax savings created by a retirement contribution; rather, the tax benefit is equivalent to effectively paying a zero rate of tax on investment returns.

Those insights are often overlooked or misunderstood, leading to inaccurate analysis and potentially harmful policy proposals. One such harmful idea is the currently popular notion of limiting the up-front benefits of tax deferral.

The Proposals

Policy analysts and lawmakers are actively interested in ideas to curtail so-called “tax expenditures”—the various code provisions that reduce taxes by granting exclusions, deductions, credits, and tax deferrals. Some want to limit these tax breaks to raise more revenue, others want to limit them to lower tax rates without reducing revenue, but the interest comes from across the political spectrum. (So, too, does opposition to eliminating these tax provisions.)

One popular approach that is portrayed as a modest compromise proposes limiting the value of tax breaks, rather than eliminating them. For example, some policy analysts propose to change tax deductions and exclusions into flat-rate 15 percent tax credits. The Obama Administration has proposed a slightly different limit: a 28 percent cap on the benefits of deductions and exclusions.

These proposals might be considered “modest” compromises if they were applied only to deductions and exclusions. For example, under current law, a $1,000 mortgage interest deduction reduces taxes by $350 for a taxpayer with a 35 percent marginal tax rate, or $250 for a taxpayer in the 25 percent bracket. But a flat-rate 15 percent credit applied to the same $1,000 of mortgage interest would reduce taxes by $150 for both taxpayers. A 28 percent cap on deductions would have even less impact: it would reduce the tax benefit for a taxpayer in the 35 percent bracket from $350 to $280, but wouldn’t affect taxpayers in the 25 percent bracket at all.

How the Proposals Would Affect Tax Deferral

But remember Insights No. 1 and No. 3: tax deferral is different from tax deductions or tax exclusions, and the benefit of tax deferral is not the up-front tax savings created by a retirement contribution. What’s “modest” for tax deductions or exclusions constitutes radical change for tax deferral.

Limiting the up-front benefit of tax-deferred contributions to retirement accounts reduces the benefits of tax deferral, but does so arbitrarily. For higher-earning workers nearing retirement, the benefits of deferral would be slashed substantially. In fact, some could find they would be better off simply paying income taxes on their wages and investing in a taxable account. On the other hand, such a limit would have a more modest impact on the benefits of deferral for young workers with higher earnings—provided they did not need to withdraw funds from the account before retirement.

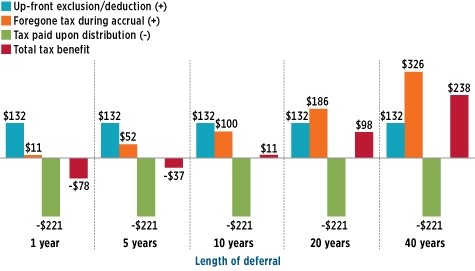

To illustrate the impact of these proposals, I’ll update the example used in the previous post (taken from The Tax Benefits and Revenue Costs of Tax Deferral) of a worker with a 25 percent marginal tax rate who defers tax on $1,000 of compensation. As a reminder, here’s the chart:

Tax Benefits Increase with Length of Deferral

Present value of tax benefit of a one-time deferral of $1,000 of compensation, by length of deferral

Note: The marginal tax rate is equal to 25 percent in all periods and applies to contributions, investment income, and distributions. Compensation of $1,000 is used to fund the contribution, resulting in a deferral of $1,000. The contribution is invested in bonds that pay interest annually. The nominal interest rate on the bonds and the discount rate are 6 percent.

Source: Investment Company Institute calculations

Under current law, provided that the worker’s marginal tax rate is the same in retirement as when the contribution was made, the tax collected on distributions (the green bar) pays back, in present value, the up-front tax benefit (the blue bar). The remaining tax benefit is that the taxpayer is effectively not taxed on the investment returns—in this case, annual interest payments of 6 percent—that would have been earned in a taxable account (the orange or red bars). That benefit rises with the saver’s holding period—from $11 for a one-year deferral up to $326 for a 40-year deferral—because the impact of taxes on investment returns increases with time.

Now suppose that the up-front benefit of deferral was limited to 15 percent. For our taxpayer in the 25 percent bracket, the limit effectively imposes an up-front tax on contributions of 10 percent. (This “contribution tax” would be even higher for taxpayers in the 28, 33, 35, or 39.6 percent brackets, of course.) The up-front limit would be the only change in tax treatment: investment returns would accrue tax-free, and, significantly, withdrawals from the account would remain fully taxable.

For our 25 percent-bracket worker, $1,000 of compensation would no longer fund a $1,000 contribution. Instead, the worker can now only fund a contribution of $882.35. The worker takes the other $117.65 as taxable compensation, subject to income tax of 25 percent, or $29.41. This leaves $88.24, which is just enough to pay the 10 percent “contribution tax” on the $882.35 contribution.

(How the exact contribution amount is derived is a bit difficult to explain without algebra. Suffice to say that $1,000 of compensation could not fund a $900 contribution, plus $25 of income tax on $100 of taxable compensation, plus a $90 “contribution tax” (900 + 25 + 90 = 1,015). And a contribution of $850 would result in money left over after paying $37.50 of income tax on $150 of taxable compensation and a “contribution tax” of $85 (850 + 37.50 + 85 = 972.50). In any case, please give me the benefit of the doubt on the amount of the contribution and continue reading.)

Limiting the up-front benefit substantially changes the benefits of tax deferral. The chart below shows how the taxpayer fares for holding periods ranging from one year to 40 years. In the year of the contribution, because the up-front tax benefit is limited to 15 percent, the worker’s income tax would be reduced by 15 percent of $882.35, or $132.35. But the taxpayer would still pay tax on distributions equal, in present value, to 25 percent of $882.35, or $220.59. So the tax collected on distributions would exceed the up-front benefit by 10 percent of the contribution, or $88.24—creating a built-in tax penalty.

Limits on the Up-Front Tax Savings of Deferral Represent a Fundamental Change in Tax Treatment

Present value of tax benefit of deferral funded with $1,000 of compensation with a 15 percent credit

Note: The marginal tax rate is equal to 25 percent in all periods and applies to contributions, investment income, and distributions. Compensation of $1,000 is used to fund the contribution, resulting in a deferral of $882.35. The remaining $117.65 ($1,000 - $882.35) is taken as taxable compensation, incurring an income tax of $29.41 ($117.65 × 25%), and leaving $88.24 ($117.65 - $29.41) to pay the 10 percent tax on the retirement plan contribution ($88.24 = $882.35 × 10%). The contribution is invested in bonds that pay interest annually. The nominal interest rate on the bonds and the discount rate are 6 percent.

Source: Investment Company Institute calculations

For shorter holding periods, the $88 built-in penalty would outweigh the benefits of effectively paying no tax on investment returns. In fact, deferral in this short-term scenario would actually increase a worker’s taxes: a one-year deferral would increase taxes by $78, while a five-year deferral would increase taxes by $37. If contributions remain invested long enough, the benefits of effectively getting tax-free investment returns would eventually outweigh the built-in penalty, but comparing the two charts shows that the benefits of tax deferral would be reduced substantially relative to current law: benefits would be reduced by almost 90 percent for a 10-year holding period and by about half for a 20-year holding period.

A Wrong Turn for Retirement

In other words, proposals to limit the up-front tax benefit of a deferral represent a significant—rather than a modest—change to the tax treatment of retirement savings. The proposals appear to be based on a misunderstanding of the benefits of tax deferral. A deferral of tax is neither a deduction nor an exclusion. Capping the up-front benefit of retirement contributions would arbitrarily penalize workers, substantially reducing the tax benefits for those closest to retirement. For a nation trying to encourage more employers to offer retirement plans and more workers to participate in them, this is simply a wrong turn.

The next post in this series will focus on the most prominent proposals to limit tax deferral, and how they unfairly target defined contribution plans.

Additional Resources:

The Tax Benefits and Revenue Costs of Tax Deferral

Other Posts in this Series:

Peter Brady is a Senior Economic Adviser at ICI.