ICI Viewpoints

Corporate and Investment Grade Bond Funds: What’s in a Name?

In the last few months, we’ve seen concerns expressed in the media, as well as by some central banks (including the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Canada) that corporate bond funds might raise financial stability concerns.

When central banks raise short-term interest rates, as the Fed is doing now, bond fund returns generally fall. The concern among regulators and reporters is that falling returns will trigger bond fund investors to redeem en masse, driving bond prices down even more. Central banks worry that that these effects could be magnified by the recent growth in corporate bond funds and their concentrated holdings in what the Fed calls “relatively illiquid corporate bond or loan holdings.”

We have heard all these concerns before. Since the financial crisis, ICI has repeatedly examined such claims and found them lacking. Over the past seven decades, bond fund investors have redeemed only very modestly during market stress. (As even the Fed notes, “widespread runs on mutual funds other than money market funds have not materialized during past episodes of stress.”) And this is no accident: fund investors are generally saving for the long term, allowing them to look through market downturns.

What’s different in this case, however, is that financial stability concerns are being inflated by confusion over what the funds in question actually hold. In fact, these funds invest nearly half their assets in Treasury and agency securities, and less than one-third in corporate bonds. In other words, these funds hold more in government bonds—traditionally the “safe haven” that investors seek in times of turmoil—than in the corporate bonds that seem to cause the regulators’ angst.

Corporate Bond Funds Have Grown, but How Much?

It is certainly true that bond funds now have a bigger footprint in the corporate bond market. During a long stretch of low interest rates, corporations have increased their borrowing, while aging investors have tilted their portfolio allocations toward bonds. But measuring that footprint requires a precise understanding of these funds and their holdings.

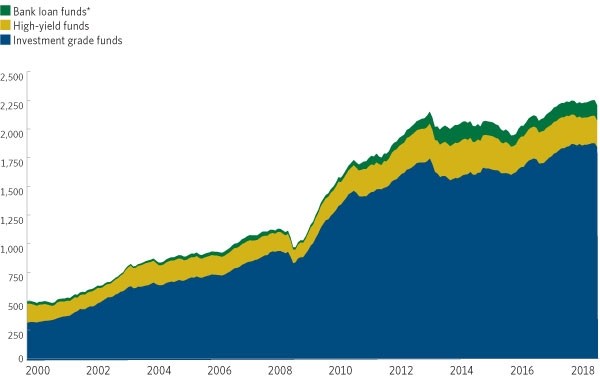

As an example, in a recent report, the Federal Reserve suggested that “Total assets under management in corporate bond mutual funds and loan mutual funds have more than doubled in the past decade to over $2 trillion.” And according to the report, the vast majority of that $2 trillion is in “investment grade corporate bond mutual funds” (emphasis added).

What the Fed appears to have measured are assets in “investment grade bond mutual funds”—a category that doesn’t include the modifier “corporate.” For example, ICI data indicate that assets in investment grade and high-yield bond funds totaled $2.3 trillion, as of September 2018. Of that, $1.9 trillion was in funds ICI classifies as “investment grade bond funds,” virtually identical to the figure the Fed cited for “investment grade corporate bond mutual funds.”

Figure 1

Assets in Selected Categories of Bond Mutual Funds

Billions of dollars (inflation-adjusted 2018 dollars), October 2018

*Bank loan funds are measured as assets in the Investment Company Institute’s floating rate high-yield bond fund category.

Sources: Investment Company Institute and Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

What’s in a name? In this case, there’s a big difference.

Investment grade corporate bond funds, as the name suggests, would likely hold the bulk of their assets in investment grade corporate bonds. Investment grade bond funds, however, can invest in any investment grade bonds—including Treasury and government agency securities.

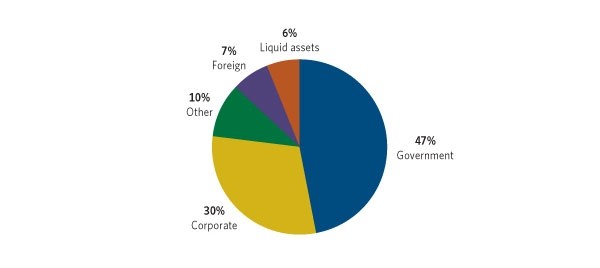

Figure 2

Portfolio Composition of Investment Grade Bond Mutual Funds

Percentage of fund assets, September 2018

Source: Investment Company Institute

And, in fact, they do. As Figure 2 shows, in September 2018, only 30 percent ($570 billion out of nearly $2 trillion) of the assets in investment grade bond funds were in corporate bonds. Almost half of those funds’ assets were in government bonds (Treasury and agency securities). The remaining assets were in foreign securities (e.g., foreign sovereign bonds), liquid assets (e.g., cash, short-term Treasury bills, commercial paper), and other securities (e.g., variable rate demand notes, asset-backed securities).

To recap: recent financial stability concerns about bond mutual funds aren’t just based on an unsupported premise about investor “runs”—they’re also inflated by imprecise terminology that invites a misunderstanding of the assets that such funds hold. A better understanding of these funds could go a long way in assuaging regulators’ and reporters’ concerns.

Sean Collins is Chief Economist at ICI.