ICI Viewpoints

As Money Market Fund Investors Adjust, Funds Have Managed Flows

Second in a series on money market funds.

The Securities and Exchange Commission’s new rules for money market funds, which must be fully implemented by October 14, largely center around two key reforms:

- Prime and tax-exempt money market funds that are sold to institutional investors must price their shares and transact using a “floating” net asset value (NAV), rather than the stable $1.00 NAV that such funds have long maintained.

- All nongovernment money market funds (i.e., prime and tax-exempt funds, whether retail or institutional) can impose delays (“gates”) or redemption fees on redeeming shareholders under limited situations. A fund is required to impose redemption fees if the fund’s weekly liquid assets fall below 10 percent of its total assets, unless the fund’s board decides a redemption fee is not in the fund’s best interests.

These changes are pushing investors toward government money market funds—those that invest principally in securities issued by the US Treasury or government agencies (or repurchase agreements backed by government securities). Institutional investors who prefer money market funds with stable $1.00 NAVs, and retail investors who want to avoid even the remote chance of redemption fees or gates, will have no choice but to invest in a government money market fund.

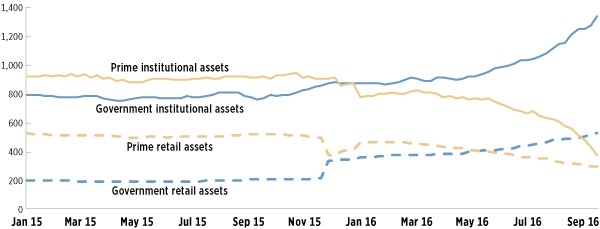

Assets Have Migrated from Prime Money Market Funds to Government Funds

Billions of dollars; weekly; January 7, 2015–September 21, 2016

Source: Investment Company Institute

Large, Ongoing Asset Shifts from Prime to Government Money Market Funds

As the chart shows, large sums have already shifted from prime money market funds—both institutional and retail—to government money market funds. According to weekly data, from January 7, 2015, to September 21, 2016, assets in prime institutional money market funds dropped $547 billion. Over the same period, assets in government institutional money market funds rose by a nearly identical amount, $544 billion.

A similar, though more muted, shift occurred in retail share classes of money market funds. From January 7, 2015, to September 21, 2016, assets in prime retail money market funds dropped $235 billion. In addition, over the same period, assets in tax-exempt money market funds—the vast majority of which are held by retail investors—fell $128 billion. Over the same period, assets of government retail money market funds rose by $328 billion.

Under the new rules, prime and tax-exempt retail money market funds may continue to transact at stable $1.00 NAVs. Thus, the shift in retail assets isn’t related to floating NAVs—it’s caused by the requirement that all nongovernment money market funds (including prime and tax-exempt retail money market funds) must now be able to impose redemption fees and gates. Indeed, industry participants report that broker-dealers, retirement plans, and other intermediaries have moved, or encouraged their clients to move, assets from prime and tax-exempt retail funds to government money market funds, to avoid any chance of facing fees or gates.

Though we can’t track the actual dollars moving from one fund to another, it seems likely that most of the $910 billion in assets that have moved out of prime and tax-exempt money market funds in response to the SEC’s rule has ended up in government funds.

How Much More Money Is Likely to Shift Before October 14?

Many large money market fund sponsors have announced the dates on which they will implement floating NAVs, ranging from October 1 to October 14. So a natural question arises: How much more money could shift from prime to government funds by October 14?

Ballpark estimates by industry participants suggest the flow could total anywhere between $200 billion and $400 billion. Estimates at the upper end of this range are not implausible. For example, as of September 21, prime money market funds still had assets of $669 billion (split as $376 billion in institutional and $293 billion in retail).

How Will the Markets Accommodate All This?

Thus far, the massive shift in assets has proceeded smoothly—and all indications are that it will continue to do so. Prime money market funds have prepared for the October 14 deadline by making their portfolios extremely liquid. As shown in the previous ICI Viewpoints in this series, the weighted average maturity on prime funds was 16 days as of September 20, 2016. This indicates that prime money market funds hold so much cash and other short-dated money market instruments that they could meet a high level of investor redemptions simply by using the proceeds from maturing securities.

On the other side of the coin, as assets in government money market funds have risen, those funds’ demands for government securities (and repurchase agreements backed by government securities) have also jumped sharply. The market seems to be accommodating the increased demand for government securities in good order. Three factors have helped.

- The Treasury appears set to continue adding to the supply of Treasury bills, in part to fund a significant rise in the Treasury’s cash holdings.

- Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs) have increased their issuance of floating rate notes (to help fund FHLB advances to banks), which government money market funds can hold.

- Government money market funds can place dollars with the Federal Reserve’s reverse repo (RRP) facility; this facility allows money market funds to make collateralized overnight “loans” to the Fed, earning interest on those loans.

In sum, although vast amounts of assets have left prime money market funds for government money market funds, and although even more will leave by October 14, the transition has been orderly—and all indications are that it will continue to be orderly. In no small part, this reflects the time and effort funds have put into transition planning and execution since the SEC adopted its new rule in 2014.

More Posts in This Series

- For Money Market Funds, Massive Preparation Has Paid Off in Smooth Transition

- As Money Market Fund Investors Adjust, Funds Have Managed Flows

- Money Market Fund Reforms Combine with Bank Regulations to Boost Interest Rates

Sean Collins is Chief Economist at ICI.