ICI Viewpoints

Across the Universe: Seeing the Whole Picture in the Systemic Risk Debate

Astrophysicists have discovered that they can’t account for the composition and behavior of the universe without including “dark matter”—matter that can’t be observed directly. New calculations show that only around 15 percent of the matter in the cosmos can be observed through today’s telescopes or other electromagnetic instruments.

There’s a parallel situation in finance. One segment of the financial universe—also around 15 percent—is more easily observed and readily measured than the rest of it, and thus tends to draw more attention. It’s sometimes even viewed as an indicator for the capital markets as a whole.

This observable financial “matter” is the regulated fund industry—U.S. mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, closed-end funds, and unit investment trusts, as well as similar funds offered in other jurisdictions. It’s not that the rest of the financial universe can’t be observed; it’s just that these other players are harder to measure and thus often overlooked, despite their dominant role in markets. Even regulators have exhibited this tendency—as seen in the Financial Stability Board’s consultation on investment funds, which effectively singled out 14 U.S.-regulated funds as the focus of systemic risk discussion in asset management.

A Small Share of Assets, a Smaller Share of Trading

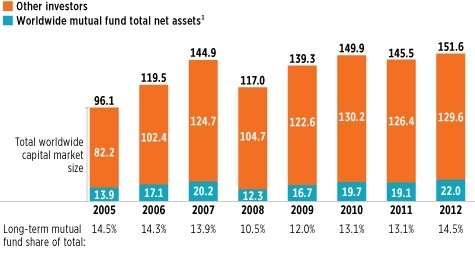

Globally, long-term mutual funds held just 14.5 percent of the market value of stocks and bonds at year-end 2012, a share that hasn’t varied significantly since 2005 (Figure 1). The other 85 percent is held by mostly institutional entities—including central banks, sovereign wealth funds, endowments and trusts, defined benefit pension plans, banks, insurance companies, hedge funds, and broker-dealers—as well as some retail investors with individual stocks and bonds.

Figure 1

Long-Term Mutual Fund Share of Worldwide Stock and Bond Markets

Trillions of U.S. dollars; year-end, 2005–2012

1Worldwide mutual fund total net assets include open-end fund assets, and for non-U.S. countries may also include exchange-traded fund (ETF) assets.

Note: Funds of funds are not included except for France, Italy, and Luxembourg.

Sources: International Investment Funds Association and International Monetary Fund

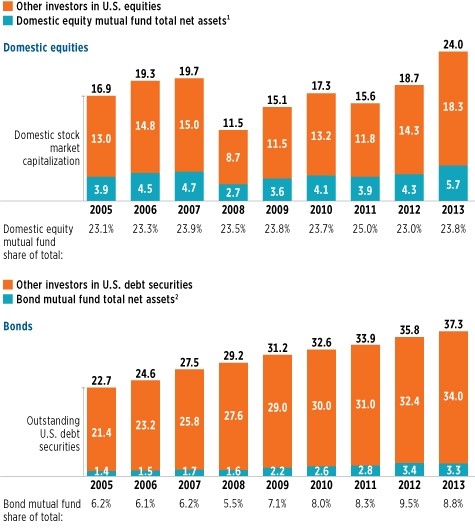

What about the markets in the United States? The story holds true there as well—as Figure 2 shows, U.S. domestic equity mutual funds (U.S.-registered mutual funds that invest primarily in U.S. equities) held 23.8 percent of U.S. stock market capitalization at year-end 2013, and U.S. bond mutual funds held just 8.8 percent of all outstanding U.S. debt securities.

Figure 2

U.S. Mutual Fund Share of U.S. Stock and Bond Markets

Trillions of U.S. dollars; year-end, 2005–2013

1Domestic equity mutual fund total net assets include assets of U.S.-registered open-end mutual funds whose investment objectives are to invest primarily in U.S. equities.

2Bond mutual fund total net assets include assets of U.S.-registered open-end mutual funds whose investment objectives are to invest primarily in debt securities.

Note: Data exclude assets in ETFs and money market funds. Components may not add to the totals because of rounding.

Sources: Investment Company Institute, Federal Reserve Board, and World Federation of Exchanges

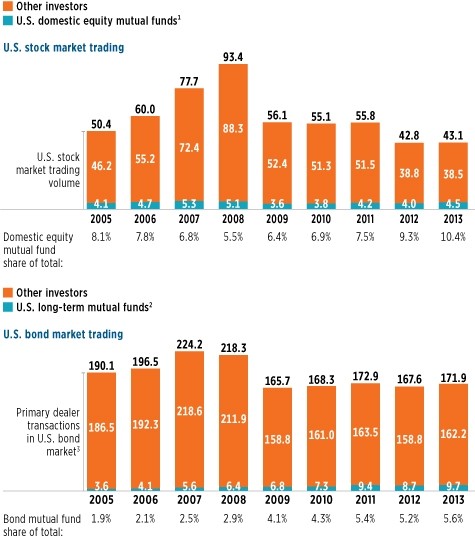

If mutual funds’ share of assets in U.S. capital markets is not particularly large, their share of trading volume is even smaller (Figure 3). U.S. domestic equity mutual funds accounted for only 10.4 percent of trading in the U.S. stock market in 2013, while U.S. mutual funds made up an estimated 5.6 percent of trading in the U.S. bond market.

Figure 3

U.S. Mutual Fund Share of U.S. Stock and Bond Market Trading

Trillions of U.S. dollars; annual, 2005–2013

1U.S. domestic equity mutual fund trades include gross portfolio purchases and sales of common stock by U.S.-registered open-end mutual funds whose investment objectives are to invest primarily in U.S. equities.

2U.S. long-term mutual fund trades include gross portfolio purchases and sales of debt securities.

3Transactions with counterparties other than inter-dealer brokers.

Note: Data exclude portfolio purchases and sales of ETFs and money market funds. Components may not add to the totals because of rounding.

Sources: Investment Company Institute, Federal Reserve Board of New York, and World Federation of Exchanges

Beyond Mutual Funds—and into the Dark Matter

Scientists have grudgingly accepted the concept of dark matter (and similarly unobservable dark energy) because they can’t explain the development and movements of stars and galaxies without it. Similarly, it’s impossible to understand the functioning and risks of capital markets without looking beyond the easily observed regulated fund sector and considering the players who account for the vast majority of holdings and trading. Focusing primarily on mutual funds would be akin to looking for lost car keys under a streetlight simply because “the light is better there.”

There’s a better approach that recognizes the role played by all capital markets participants, lighted and dark. Regulators charged with reducing systemic risk should take an activity-based approach—focusing on activities and practices that occur across the entire universe of financial markets—rather than singling out particular sectors or firms for designation as “systemically important.” Under an activity-based approach, regulators address any risks that they perceive with solutions that apply to all players in the markets and that relate directly to the identified activities.

For activities involving the capital markets, regulators with relevant experience and expertise—such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)—should drive the process, identifying issues and considering appropriate solutions. Under this process, regulators would adhere to standard rulemaking procedures, including public meetings (with advance notice and reporting after), opportunities for the public to comment on proposals, and requirements to apply rigorous cost-benefit analysis.

Regulators’ rulemaking authority was substantial before the financial crisis, and was further strengthened by the Dodd-Frank Act. SEC Chair Mary Jo White confirmed at an April 2014 congressional hearing that the commission has all the authority it needs to regulate the asset management industry adequately. Supervision of asset managers by banking regulators—whose approach is to address concerns about capital markets through bank-like regulations—is neither necessary nor constructive.

Just One Part of the Markets

U.S. mutual funds are highly transparent and easy to track because of regulatory disclosure and because a number of organizations—including ICI—gather and publish data on fund assets, flows, portfolio holdings, returns, and much more. These funds have opened up the capital markets for more than 95 million Americans and created an investment culture that lets workers and savers reap the benefits of owning shares in businesses across the world. But the downside to success and transparency may be attention out of proportion to potential risks.

Capital markets have long played a critical role in helping economies grow. Numerous types of players—and innumerable types of activities—have a place in these markets, and mutual funds are just one type. Any search for systemic risk must take that diversity into account.

Paul Schott Stevens was President and CEO of ICI.