ICI Viewpoints

Allegations Made in Indiana University Study Are Speculative and Dubious

Thanks to mutual funds’ structure and regulation, fund investors enjoy a number of protections. One among them is that advisers to funds, as well as directors on fund boards, have fiduciary duties. This means they have a fundamental, legal obligation to act in the best interests of the fund—and its shareholders—with undivided loyalty and utmost good faith.

Therefore, it is alarming to hear of a forthcoming academic study, authored by professors at Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business, alleging that funds are consciously shirking their fiduciary duties. A press release promoting the study declares, “mutual fund families deliberately sacrifice performance of some funds to shore up losses elsewhere.” A media commentary that followed that press release ominously warned readers, “This investment could cost you…Fund of funds may put firm’s interest ahead of yours.”

On closer inspection, however, the allegations here rest largely on speculation. They don’t ring true for those who understand how funds operate and are regulated.

The Subject of the Study: Proprietary Funds of Funds

The topic of this paper is funds of funds—mutual funds that invest in other mutual funds. In particular, the authors address proprietary funds of funds, meaning funds where both the overarching fund and its underlying component funds have the same sponsor. For example, a target retirement date fund from fund Company X might allocate its holdings between Company X’s own stock, bond, and international index funds. By contrast, nonproprietary funds of funds invest in funds offered by other fund sponsors. In either case, funds of funds can be passively managed, where allocations are relatively fixed, or actively managed, where a fund manager may have slightly more discretion to change investment allocations based on his or her assessment of market conditions.

In essence, the study argues that managers of proprietary funds of funds direct capital to prop up “distressed” underlying funds, thus sacrificing “their own shareholders’ interests for the benefit of the family.”

What’s the basis for this charge? One might assume that the researchers used actual trading information to gather evidence of investment intent, revealing why funds made particular investment decisions. And that they excluded passive funds of funds, such as target date funds in which asset allocations are rebalanced according to a predetermined glide path. But the researchers did nothing of the sort. Instead, they lumped all proprietary funds of funds together, whether active or passive, target date or not, and attempted to draw inferences about quarterly or monthly fund flows based on a statistical analysis of changes in assets under management and reported returns.

This approach strikes us as overbroad and speculative, telling us little to nothing about the intent behind portfolio management decisions made by a fund of funds manager. Perhaps the final published version of this paper will have a different methodology that inspires more confidence in its findings. This version’s methodology certainly does not.

Legitimate Investment Factors at Work

Still, we take seriously any charge that a fund might be investing assets for reasons other than the best interests of its investors. Here, that charge is that the funds of funds invest more heavily in underperforming, so-called distressed funds. The authors define “distressed” for these purposes to mean underlying funds that, based on their flow data, appear to face the largest outflows from outside investors.

As the study itself acknowledges, legitimate investment practices explain why funds of funds might invest more heavily in one fund over another. Let’s look at two.

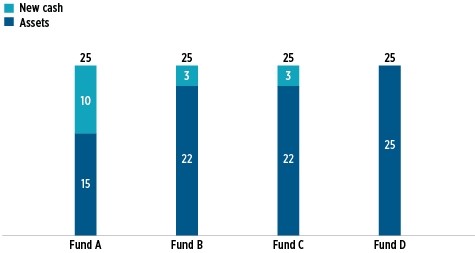

- Reallocating: Whether actively or passively managed, many funds of funds rebalance their holdings to maintain their investment allocations and carry out their investment mandate. To take a thumbnail example, suppose a fund of funds had four underlying funds, each with 25 percent of its allocation. Suppose that one of the underlying funds has performed worse than the others (Fund A in the example below), one fund has performed better (Fund D), and the others (Funds B and C) have been flat. In accordance with its investment guidelines, the fund of funds now needs to rebalance, so that all four funds have a 25 percent share of the portfolio. It can do so by deploying new money coming into the fund, putting most of the new money into the poorly performing fund (Fund A) to raise it back up to 25 percent of the portfolio. The flat funds (Funds B and C) would receive some cash, and the fund that has performed well (Fund D) would receive none. Simple rebalancing would explain why the manager has invested most of the fund of funds’ available cash in the worst performing fund.

- Buying Low: For funds of funds that are actively managed, there may be times when the fund’s portfolio manager takes a contrarian approach, buying assets that others are selling. Poor short-term performance of an underlying fund may present a long-term buying opportunity, and may give the fund of funds manager a chance to actively increase its investment exposure.

Study’s Allegations Don’t Square with How Funds and Portfolio Managers Operate

Although conflicts of interest could arise in a fund of funds, funds take numerous steps to ensure that portfolio managers stay true to their investment mandates and the fiduciary duties owed to the fund and its shareholders.

For example, fund boards act as independent watchdogs, protecting the interests of fund investors. It would be impossible for a board, consistent with its fiduciary duty, to sign off on a decision to “sacrifice” the performance of one fund for the benefit of other funds in the complex. Boards, which include independent directors, have a separate obligation to each fund that they oversee—not the fund complex as an entity.

Moreover, in our experience, portfolio managers generally are not the types to “take one for the team,” as alleged. The fund managers we’ve met take their fiduciary duties very seriously, and have every incentive (compensation and otherwise) to produce the very best performance results they can for the funds that they manage.

In their press release, one of the study’s authors says he finds it “baffling” that fund managers would sacrifice their own funds’ performance. On that, we completely agree.

This Kind of Behavior Would Be Very Easy to Detect

Finally, these charges fail still another test of common sense. If funds of funds managers were committing this sort of wrongdoing, it would be very easy to detect for anyone with access to a fund’s trade blotter. And there are people with such access, including funds’ internal compliance teams, who regularly review trading activity, and the inspection and enforcement staffs of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Wrongdoing does happen, of course. But in this case, what’s alleged in this study looks dubious at best. In our view, strong oversight, the strength of fiduciary duty, legitimate investment practices, and common sense trump sensational charges that rest on a flawed approach.

Bob Grohowski was a Senior Counsel at ICI.